AN AMERICAN MOVIE MADE IN AUSTRIA? That’s Haneke’s description of Funny Games, and his explanation of why he’s remaking it in Hollywood.

|

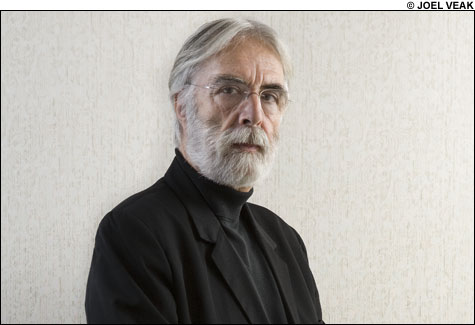

A couple of weeks ago at the Oscars, the first Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film to go to an Austrian went to the wrong filmmaker. Stefan Ruzowitzky’s Die fälscher|The Counterfeiters was polished, trite, and inoffensive. Qualities that the films of Michael Haneke are everything but.

Caché (2005), for example — the film that brought Haneke to the attention of a broad circle of cinephiles here in the US. Meticulous, enigmatic, it exposed the hidden guilt and hypocrisy of the middle class. Or, more provocatively, Funny Games (1997), which not only assaulted the complacency of the bourgeoisie but also took a shot at the media and even at its own audience.

But now Michael Haneke has gone on to Hollywood. He’s remaking Funny Games, repeating it shot for shot with a stellar cast that includes Naomi Watts and Tim Roth. It opens next Friday. In town last October for a retrospective of his films at the Harvard Film Archive, he discussed this career move, as well as media violence, the legacy of the ’60s, and the Hollywood remake of Caché that might be in the works — but not his uncanny resemblance to Phoenix classical-music reviewer Lloyd Schwartz.

When I heard that you were remaking Funny Games, I thought of how George Sluizer made his very successful little European film The Vanishing into a Hollywood movie that wasn’t so successful.

For me, the first Funny Games, the one in Europe, was meant for consumers of violence, and it was a slap in the face for these people. . . . So when I had the possibility to do it in English, I took the opportunity. And now the film has arrived at the audience that it was meant for. It was meant for the United States to begin with, because Funny Games has an English title. The house in the German version is like no house in Austria is like. It was a set. We tried to imitate a classic American colonial house with the center staircase. And so there was a reason for doing the remake, so when I was offered the chance, I said, sure, I’d love to do it, but only if Naomi Watts is going to play the lead

Is it different because 10 years have passed and there are different connotations and historical contexts?

In some ways, I feel that the film has become more up to date because violence in the media, if anything, has increased, and the senseless consumption of it. I mean, you had to do nothing different, you had to change nothing, and it became more apropos. And the social level I am describing is the same all over the world. Whether they are in Austria or in the United States, they are a well-educated, cultivated, and blasé bourgeoisie. In other words, the people from which I come.

I was thinking of the scene with the kid with the pillowcase over his head — Abu Ghraib crossed my mind.

It was actually on the poster of the first Funny Games, and it was way before Abu Ghraib, but the associations of course have multiplied.

So do you think Funny Games inspired Abu Ghraib?

You don’t need to inspire these kinds of things. You don’t need to tell people how to commit violence. When the first film came out — well, it had not come out yet, it was finished, but nobody had seen it yet. There was an article in Der Spiegel about a case in Spain where two young men got white gloves [part of the MO in Funny Games], very polite, the whole thing, and tortured a family — one person to death.

When the movie came out, they probably started blaming you for it.

It’s interesting to see the parallels, because the two young men that did that, in reality, were two well-educated people [like the culprits in the movie]. One was a student of chemistry, and when he was put in jail, he actually wrote a very intelligent essay. He quoted Nietzsche and everything and the worthlessness of life. The victims deserved to die, he argued, because there is no point to existence.

But you also suggest in your films that there’s an alienation effect that images and video and the whole culture seem to have that might lead to such behavior.

Our understanding of reality is based on television nowadays, and that’s of course very dangerous, because the images are not reality. So I always in my films try to nourish some distrust in taking this reality for granted.

Do you watch TV?

Not so much. It’s too boring. The programming gets worse every day — not as bad as in America, but nearly.